Some of my favorite writings from Ernest Hemingway aren’t in his books or his short stories. It’s his writings as a reporter and how he uses suspenseful introductions in his work.

For much of his career, he wrote for newspapers and magazines. It’s how he defined and harnessed his craft. His punchy, direct, and simplistic prose made him the legend he is today.

I enjoy reviewing these works because they are often short and packed with his early writing techniques. We can learn a lot from Ernest Hemingway, like how he started his stories and captured an audience through his suspenseful introductions.

In his article “A Free Shave” published in The Toronto Star Weekly, on March 6th, 1920, he makes something insignificant interesting for readers.

Here is an excerpt on how he starts the story:

“The true home of the free and the brave is the barber college. Everything is free there. And you have to be brave. If you want to save $5.60 a month on shaves and hair cuts go to the barber college, but take your courage with you.

“For a visit to the barber college requires, cold, naked, valor, of the man who walks clear-eyed to death. If you don’t believe it, go to the beginner’s department of the barber’s college and offer yourself for a free shave. I did.”

Before we jump into the story, consider how Hemingway takes something as simple as a free shave into a dramatic, life-threatening event.

First, he puts the reader in the story. He tells us we have to be brave to get a free cut. We need to bring our courage with us.

Your first impression might be that the author is exaggerating. But Hemingway pushes on with colorful adjectives and descriptions. “…a visit to the barber college requires, cold, naked, valor, of the man who walks clear-eyed to death.” It reminds me of the setting established at the beginning of Moby Dick that drives readers to dive into the world of whaling.

Notice Hemingway still doesn’t tell us what’s going on. He finally dares us to visit the beginner’s department at a barber school. This is an official invitation to the story.

But when does this introduction become a story? It starts with two words. “I did.” After his challenge for readers to experience a free cut from a beginner, he tells them he already did.

What can we learn from this suspenseful introduction?

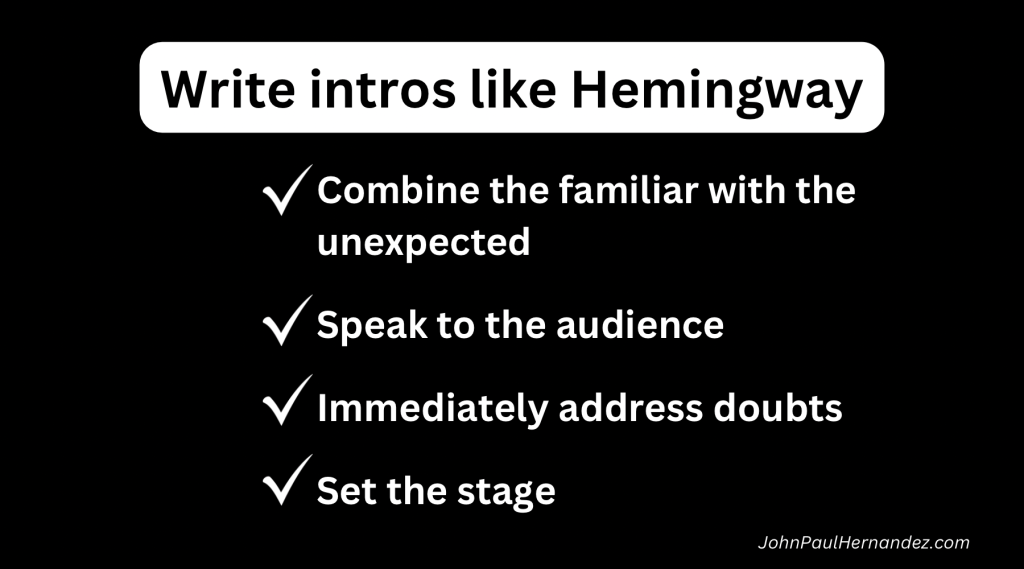

1. Combine the familiar with the unexpected

The article starts off talking about “land of the free and home of the brave”, an American phrase deeply rooted in its creation and origins. While writing to a Canadian audience, it still hits close to home for its readers.

Then he combines our idea of “free” with free shaves or cuts. But naturally, we never think of it as brave. Hemingway introduces the concept and persuades us on why we should think so.

This serves as a strong and unexpected hook. If you want to drive curiosity, find something that is deeply rooted in culture and parallel it with something brand new.

2. Speak to the audience

Whether you are writing or telling your story, direct your introduction to them. A story invites the reader.

Think about the last time you read an interesting novel that sucked you into the plot. You likely put yourself in the story, relating to the protagonist or a character in the book. When you imagined the story, you saw yourself in it.

Hemingway does a great job of this when he points to his readers about bravery and courage.

3. Immediately address doubts

If you’ve tried to write fiction, one of the biggest doubts you’ll have is whether readers will believe in you or not.

Is your story believable? Would they believe this character would go through a risk like that to save his career?

Hemingway’s article, a work of journalism, does the same thing. Most of us would doubt the risk and bravery of a free shave. Ernest knows it. He talks to us when he says “…if you don’t believe it, go to the beginner’s department…” But he adds even more credibility when he says “I did.”

4. Set the stage

Hemingway uses all three techniques mentioned above to set the story. He has not started it. He’s adding more weight to a free shave experience and making it life-threatening. This dramatic shift is what makes the story suspenseful.

Not only is it the way he raises the bar and its risks before the plot, but it’s how he makes the mundane interesting.

If someone told you a story about a bank robber, it would be suspenseful but you might not get through the introduction because you imagine it’s like the other hundred bank robber stories you’ve heard in the past.

But if that person tells you a story about how a grandmother walked away with $20,000 of stolen money, never detected or caught, you’ll want to know how it was done. It’s not suspense of adrenaline, it’s an authentic curiosity of the unknown.

The rest of Hemingway’s story

If you read the rest of the article, available online, you’ll learn how Hemingway stays true to his introduction, because if you are going to promise something big in your story, make sure to follow it through.

He continues to add suspense, like how the barber he got was demoted to the beginner’s department because of a shaving accident that lacerated his thumb that same morning.

What style of writing did Hemingway introduce?

Hemingway mastered the art of saying more with less. His writing was sharp, direct, and packed with meaning beneath the surface—a technique known as the Iceberg Theory. Instead of spelling everything out, he let the reader fill in the blanks.

His background in journalism shaped his punchy, no-nonsense style. He skipped the fluff and got straight to the point, using vivid details and action to pull readers in. Whether he was writing about war, fishing, or a barber college, you felt like you were there.

For marketers and B2B writers, there’s a big takeaway: clarity wins. You don’t need fancy words or long explanations. Just make every word count.

—–

As you develop suspenseful introductions, use these tips to help guide your process. Find a way to make something familiar into something irresistible that begs your audience to say “tell me more.”

If you’re a B2B SaaS looking for a content writer, click here to contact me for more information.